Shipwrecks Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

Plate Fleets

The vast amounts of natural resources discovered in the New World inspired envy among Spain’s European rivals, especially France and England. Spanish shipments of silver ( plata ), gold, gems, spices, and other exotic goods soon became prey for pirates and corsairs intent on stealing their share. To counter this threat, Spain developed a formal convoy system as early as 1537 to protect its merchant vessels from predators. At least two armed escorts, a capitana or flagship sailing at the front of the fleet and an almiranta or vice-flagship in the rear, accompanied the heavily laden ships across the Atlantic. Additional armed galleons often protected large fleets. To pay for this protection, merchants whose cargos were carried in the fleet paid a tax on their goods to the Spanish Crown. Over the years, the tax increased from 2 percent in the sixteenth century to 12 percent by the seventeenth century, a reflection of the increasing difficulty of protecting the ships.

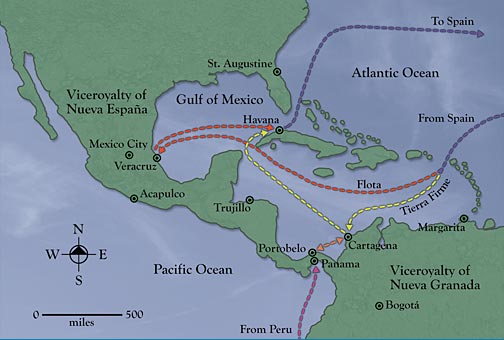

Each year, two separate fleets left Spain loaded with European goods that were in great demand in the Spanish-American colonies. Sailing together down the coast of Africa, the fleets stopped at the Canary Islands for provisions before the long voyage across the Atlantic. Once they reached the Caribbean, the fleets separated. The New Spain fleet, or flota, sailed to Veracruz in Mexico to take on silver and other goods, as well as porcelain shipped from China on the Manila galleons and brought overland from Acapulco by mule train. The Tierra Firme fleet, or galeones, made for Cartagena to take on South American products. Some ships were sent to Portobello in Panama to pick up Peruvian silver, while others went to the island of Margarita to collect pearls harvested from offshore oyster beds. Once loading was completed, both fleets sailed for Havana, Cuba to rendezvous for the journey back to Spain.

The ships leaving Havana were crammed full of New World products. Gold and silver in coins and bars, property of the king, were carried aboard the heavily armed escort galleons. Personal wealth in coins and jewelry accompanied passengers on the merchant ships, together with indigo and cochineal dyes, exotic woods, ceramics, leather goods, chocolate, vanilla, sassafras, tobacco, and products made by the native peoples of the Americas.

The fleet faced many dangers as it slowly made its way back to Spain. Uncharted reefs and shifting sandbars, treacherous currents, wily pirates, and unexpected storms all took their toll on the fleets. Wooden ships also were victims of tropical shipworms that bored through planks, making the vessels leaky and unseaworthy. In many cases, the ships of the plate fleets were old and nearing the end of their serviceable careers, sent to the New World by owners hoping to complete just one more profitable voyage. One of the greatest fears was hurricanes. With no way to forecast the storms or to predict their tracks, ships were completely at the mercy of wind and waves.

Over the years of the fleet system, which lasted until nearly 1800, Spain managed to transport enormous amounts of goods and materials between Europe and the New World. Some ships inevitably were wrecked along the way and the Spanish developed effective salvage capabilities to recover the valuable cargos. The remains of these ships now provide us with exceptional opportunities to study our maritime past, and offer divers and snorkelers exciting underwater adventures.